S3: Languages and their place in human affairs. Semiology (P15 – 17)

N: Why is Semiology not yet a word in MS word’s dictionary?

N: In these two pages, Saussure famously proposed the science of Semiology: a science studying signs and its role as part of social life. This section is highly philosophical, and contain some inconsistency which I believe arise from issues with translation. It is worth reading the section in its entirety again and again to understand Saussure’s essential thoughts on the issue of language and sign.

Q: A language, defined in this way from among the totality of facts of language, has a particular place in the realm of human affairs, whereas language does not.

N: Here, what Saussure meant by “A language” is a language as a structure system, whereas “language” is the act of communication, primarily by speech.

Q: A language, as we have just seen, is a social institution. But it is in various respects distinct from political, juridical and other institutions.

N: We should compare the language phenomenon to economy.

Q: A language is a system of signs expressing ideas, and hence comparable to writing, the deaf-and dumb alphabet, symbolic rites, forms of politeness, military signals, and so on.

N: What seems strange to me is the fact that Saussure separate writing from language. As a Chinese native speaker, I have always considered writing as an integral and inseparable part of a language. I also tend to view the systems which Saussure listed as “comparable” as a form of language. Could it be that my view of language is closer to what Saussure would consider as a system of signs?

N: If we understand any system of signs as a form of language, is there really a need for a separate discipline called “semiology”? Should we not also include the study of various sign system into the linguistic discipline? Anyway, this is an ontological question and should not be the concern of linguists. The crux of the matter is, if a language is a system of signs, and the most important and obvious system of signs is language, then it stands to reason that the study of the two is the same in fact, if not categorical.

Q: … hitherto a language has usually been considered as a function of something else, from other points of view… there is the superficial view taken by the general public, which sees a language merely as a nomenclature. This is a view which stifles any inquiry into the true nature of linguistic structure.

N: Nomenclature: the devising or choosing of names for things, especially in a science or other discipline; A naming system.

N: Language is obviously not just the naming of things, but it is also correct to say that one of the most important function of language is to give names to things; it probably began as such.

Q: …the viewpoint of the psychologist, who studies the mechanism of the sign in the individual. This is the most straightforward approach, but it takes us no further than individual execution. It does not even take us as far as the linguistic sign itself, which is social by nature.

N: The dialectic relationship between the individual and the collective must be observed in all phenomenon; The individual is part of the collective; yet the collective is formed of individuals. Without the individual, there is no collective, and without the collective, the individual cease to be necessary. The individual and the collective is only meaningful in relation to each other.

Q: … to the fact that the sign must be studied as a social phenomenon, attention is restricted to those features of languages which they share with institutions mainly established by voluntary decision.

N: The grammarians…

Q: In this way, the investigation is diverted from its goal. It neglects those characteristics which belong only to semiological systems in general, and to languages in particular. For the signs always to some extent eludes control by the will, whether of the individual or of society: that is its essential nature, even though it may be by no means obvious at first sight.

N: What Saussure means is that if we only study the features of languages which is established voluntarily, we risks missing those features of language which develop organically from its usage. It is all fine to study the “official”, “correct”, “standardize” form of the language and its related social institution, but when language is used in our daily lives, it takes on its own lives, and eludes the control of human will. In this sense, it is very similar to human economy, or any such mass system.

Q: If one wishes to discover the true nature of language systems, one must first consider what they have in common with all other systems of the same kind. Linguistic factors which at first seem central must be relegated to a place of secondary importance if it is found that they merely differentiate languages from other such systems.

N: This sheds some light into the teaching of language. It is not the vocabulary (the names) , the pronunciation (vocal component), and even the grammar (rules of using a language) that is the most important components in a language, although they are necessary. It is the structure of the language which will enable a person to finally grasp the usage of a language. And because the nature of language structure is common across all languages, people who are able to really understand a language, will be able to achieve similar proficiency in another language, given sufficient material (linguistic inputs). We observe this as a kind of “linguistic aptitude” which measures an individual’s capability to use languages.

CHAPTER IV: Linguistics of Language Structure and Linguistics of Speech (18-20)

Critical Summary:

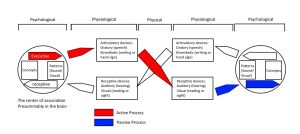

In these three pages, Saussure attempts to differentiate the actual act of using the language in speech from what he termed the “linguistic proper”, I.e. the linguistic structure. He attempted to draw the distinction between studying the actual use of a language itself and studying the linguistic structure.

This distinction can be made apparent by comparing a language which relies on speech act as we know it, to a language which is not reliant on speech, like the sign language. Although these languages have different forms of expression, they can express the same idea, which is translated into a language structure which only correspond to the expression of meaning.

This distinction is also apparent to anyone who is familiar with the Chinese language and its writing system. It is common knowledge that in the Chinese language, the same writing system can produce speeches which are vastly different from each other in different dialects. The writing system correspond directly to the linguistic structure, which contains its essential meaning. The speeches in different dialects are merely different expression of the same structure. The studies of the different speeches in Chinese would correspond neatly and directly to Saussure’s idea of a “linguistic of speech”, whereas the study of the Chinese language as shown in its writing responds to his idea of a “linguistic of language structure”, or “linguistic proper”.

However, even Saussure himself noted that even though it is possible to draw a distinction between the two, in actual application the two is inseparably intertwined, and it is close to impossible to study one without referring to another. This apply to other acts of language too.

In summary, it is important to establish the object of study of linguistic as the linguistic structure. It is important to observe at the same time that it is impossible to study the structure without the substance of language, which is observed in the actual act of using the language itself.

Q: The activity of the speaker must be studies in a variety of disciplines, which are of concern to linguistics only through their connexions with linguistic structure.

Q: The study of language thus comprises two parts. The essential part takes for its object the language itself, which is social in its essence and independent of the individual. This is a purely psychological study. The subsidiary part takes as its object of study the individual part of language, which means speech, including phonation. This is a psycho-physical study.

Q: The two objects of study are doubtlessly closely linked and each presupposes the other. A language is necessary in order that speech should be intelligible and produce all its effects. But speech also is necessary in order that a language may be established… it is by listening to others that we learn our native language. A language accumulates in our brain only as the result of countless experiences… Thus there is an interdependence between the language itself and speech. The former is at the same time the instrument and the product of the latter. But none of this compromises the absolute nature of the distinction between the two.

N: Note the primacy associated with speech. Although undeniably, the speech act is a major part of a language, there are other forms of expression, some independent of the speech act. For instance a pictorial writing system.

N: Also from the angle of language learning, if the speech act is so important, it follows that listening and speaking should form an important part, if not the predominant part of language teaching. For Chinese, writing should gain the same importance, because of how the writing system directly correspond to the linguistic structure in the Chinese language.

N: From the act of language learning, what is more important? How can it relate to the linguistic structure? How can linguistic structure shed light on how a language should be taught and learned?

Q: A language, as a collective phenomenon, takes the form of a totality of imprints in everyone’s brain, rather like a dictionary of which each individual has an identical copy…

N: This is a rather disputable statement; For each individual’s understanding and grasp of a language, even among native speakers, is different from one another. So does it mean that we should exclude the parts where everyone has a slightly different appreciation from “linguistic proper”, or simply assign differences as different languages (Should Am.E and Br.E be considered as TWO separate languages or two variants of the same language?). Or rather, this statement is fundamentally indefensible, and that we have to accept that despite a basic linguistic framework, there exist different level of understanding and appreciation in each individual’s “linguistic” imprints, and that a language which comprise the totality of imprints in everyone’s brain of which each individual has an identical copy is merely a theoretical possibility, but not an actual one?

N: If the above statement is true, there would be no misunderstanding in the world.

Q: In what way is speech present in this same collectivity? Speech is the sum total of what people say, and it comprises (a) individual combinations of words, depending on the will of the speakers, and (b) acts of phonation, which are also voluntary and are necessary for the execution of the speakers’ combination of words. Thus there is nothing collective about speech. Its manifestations are individual and ephemeral. It is no more than an aggregate of particular cases…

N: In here, Saussure’s “speech” clearly meant the application of a language in an act of speech. Thus, he is correct to observe that it is individual to the speaker and is particular to the situation. However, this makes his statement of a universal collective “language” which is identical in everyone’s brain a rather stark statement, because if we form our linguistic imprint based on the speech we hear, and that the speech we hear is of an individual and varied nature, how is it possible that we can form an identical linguistic imprint in our minds?

Critical analysis:

I suspect the failing of this Chapter is not one of ideation, but one of expression or perhaps of translation. It is clear that there must be enough common element in everyone’s “linguistic imprint” to make “a language” a reality, yet there also exist sufficient differences in our “linguistic imprint” which produces error of speech, variants of the same languages, and even misunderstanding in our actual use of language. Saussure attempts to get at the common core by differentiating the elements of individual character in a language. He might have termed it in a way which invites controversial, but his underlying logic and reasoning is sound, and what is important is we understand the underlying logic, and his observation that the common core of a language to every person is its “linguistic structure”.

CHAPTER V: Internal and External Elements of a Language (P21-23).

Critical summary:

In these three pages, Saussure recounts the different elements which influence the use of language, including other social institution, and explain that although these different elements affect language as a phenomenon, they are external to the study of linguistic system. The sole object of linguistic studies should be its Internal elements, which is the linguistic system itself. This is a very important chapter which clears up the confusion facing many students of linguistics.

The external elements which Saussure listed includes: ethnology, political history, other social institutions, literary languages, dialects, and geography.

Saussure went on to make an excellent argument in the necessity of separating these external elements of a language from its internal elements (the linguistic proper), while remaining conscious and aware of its influences.

Some of the important quotes and a critical analysis follows:

Q: A nation’s way of life has an effect upon its language. At the same time, it is in great part the language which makes the nation.

N: The importance of this observation cannot be overstated. When a person adopt a language, it adopts along with the language a way of thinking and a way of life. It might not be apparent at first, but its effect is far reaching.

Q: Major historical events… are of incalculable linguistic importance in all kinds of ways.

N: One familiar with Chinese history can immediately point to the Unification of China under Qin Shi Huang as a significant development in the history of Chinese language.

Q: A language has connexions with institutions of every sort… These institutions in turn are intimately bound up with the literary development of a language… A literary language is by no means confined to the limits apparently imposed upon it by literature…

N: Courts, academies, salons, governments, etc, these social institutions, in their use of language, leave their imprint in the daily use of our language, and in return, the common parlance also has influence in the language used in these institutions.

Q: … there arises the important question of conflict with local dialects. The linguist must also examine the reciprocal relations between the language of books and the language of colloquial speech,

N: This is important in defining the objective of language learning: What is the primary goal of the language education system?

Q: …every literary language, as a product of culture, becomes cut off from the spoken word, which is a language’s natural sphere of existence.

N: That’s why it is not sufficient to just write; An idea must be propagate through the speech act!

Q: Finally, everything which relates to the geographical extension of languages and to their fragmentation into dialects concerns external linguistics. It is on this point, doubtless, that the distinction between external linguistics an internal linguistics appears most paradoxical. For every language in existence has its own geographical area. None the less, in fact geography has nothing to do with the internal structure of the language.

Q: It is sometimes claimed that it is absolutely impossible to separate all these questions from the study of language itself. That is a view which is associated especially with the insistence that science should study ‘Realia’.

Q: In our opinion, the study of external linguistic phenomenon can teach linguists a great deal. But it is not true to say that without taking such phenomena into account we cannot come to terms with the internal structure of the language itself.

Q: The main point here is that a borrowed word no longer counts as borrowed as soon as it is studied in the context of a system.

N: To the system, where its individual parts originate from has no bearings on the system as a whole. A language system which can adopt components from different sources is no doubt a most adaptable system.

Q: In any case, a separation of internal and external viewpoints is essential. The more rigorously it is observed, the better… each viewpoint gives rise to a distinct method.

Q: Everything is internal which alters the system in any degree whatsoever.

Critical analysis:

Saussure’s view of a language as a self-contained system is a sound one, however, it can be easily misconstrued, and very hard to give a definite shape. For instance, what is considered as the system? Is it the structure itself? In many languages, there exist the phenomenon where a subject is sometimes omitted based on the context of the discourse. Does it mean the system is being altered? The ‘system’ of a language should not be viewed narrowly as containing only its structure, although the structure is a big part of it. The system also contains the rules of the construction of its structure.

In a sense, the study of the linguistic system is a study of the human mind itself. Because what we perceive and experience in the material is translated by our mind into a language. The linguistic system is thus the closest object we have to study which is the equivalent of the human minds.

To take it further, the relation between the external and internal elements of language, is parallel to the relation of the development of human mind and our external experience of the material world: one is not possible without another, yet are clearly distinct from each other.

In the practical point of view, there is a need to draw the distinction between ‘grammar’ and the internal system of a language. The two can be deceivingly similar, yet are completely different.